Contact Zones.

The Arctic / Amazon project supports and strengthens the exchange of knowledge between Indigenous communities from richly diverse and geographically remote regions, grounded in traditional knowledge that exists across time and space. Through open dialogue and collaboration, artists and authors gather to exchange perspectives and knowledges in cultural contact zones.

Knowledge Exchange Workshop.

For the Workshop on Contact Zones, Gerald McMaster and Nina Vincent are joined in conversation by Tanya Lukin Linklater to engage in a dialogue on the Reclamation of Traditional Knowledge and the notion of the Museum as a Contact Zone. The workshop also touches on the Knowledge that exists in cultural belongings and the extensive Land Based Artwork of Lukin Linklater with her community in the Alutiiq villages of the Kodiak Island archipelago of southwestern Alaska.

Tanya Lukin Linklater

Tanya Lukin Linklater is Supiaq/Alutiiq and her homelands are in the Kodiak Island archipelago of southwestern Alaska. Her performances, works for camera, installations, and writings have been shown at Soft Water Hard Stone, the 2021 New Museum Triennial, Soft Power at SFMOMA, ….and other such stories, the Chicago Architecture Biennial 2019, and elsewhere. In 2021 she received the Herb Alpert Award in the Arts for Visual Art.

Resource Package.

The Arctic/Amazon digital resource is a free educational tool, featuring an abridged version of the Arctic/Amazon: Networks of Global Indigeneity Epistolary Exchange and a series of four virtual Knowledge Exchange Workshops led by the two principal authors – Dr. Gerald McMaster and Dr. Nina Vincent. This document is offered by Wapatah Centre for Indigenous Visual Knowledge as part of the publicly available digital resource and as a companion online tool accessible alongside the Arctic/Amazon: Networks of Global Indigeneity publication.

Arctic/Amazon: Networks of Global Indigeneity is co-authored and led by Dr. Gerald McMaster and Dr. Nina Vincent.

Dr. Gerald McMaster

Gerald McMaster, O.C., is one of Canada’s most revered and esteemed academics. He is a curator, artist and author, and is currently professor and Tier 1 Canada Research Chair of Indigenous Visual Culture and Curatorial Practice at OCAD University, where he leads a team of researchers at the Wapatah Centre for Indigenous Visual Knowledge. He is nehiyaw (Plains Cree) and a citizen of the Siksika First Nation.

Dr. Nina Vincent

Nina Vincent is a Brazilian anthropologist currently working at the National Institute of Historical and Artistic Heritage (IPHAN). Her work focuses on intangible heritage preservation, museum studies, intersection of contemporary art production and community partnership building, Indigenous art and knowledge, and cultural perceptions of nature and politics.

EPISTOLARY FOUR: CONTACT ZONES AND THE INTERPRETATION OF LANGUAGE

Dr. Gerald McMaster

Many First Nations and Indigenous can relate to being called something different than what they call themselves. Often such terms are derogatory. In the case of Inuit, the term “Eskimo”, is generally known to mean “eaters of raw meat.” While it is true the Inuit did eat raw meat and continue to consume certain types of it, many other Indigenous hunting communities across the continents also participate in this type of practice. As is often the case, hunters will often eat an intestinal part, such as the liver of their kill, as a sign of success, and life, but also to honour the death of the animal.

“Eskimo” term still survives amongst Indigenous people in the US state of Alaska. In contrast, as an encompassing term, Inuit, covers a much wider area. No such term exists for First Nations that can be considered original or one that predates early contact. Europeans were quick to apply the term “Indian.” This was strategic in that it erased the diversity and complexity of the American continents and rendered the rich histories and peoples into a group abstraction that denied societal agency and complexity. Their genealogy of ascribing names has always been controversial, to the degree that colonial governments, even those more modern versions pace the 1982 Canadian Constitution, institutionalized a practice of common denominator nomenclature. In response, we see Indigenous communities, such as Inuit, revert to the names they have always called themselves.

Similarly, in Scandinavian countries where Sami are Indigenous, they were once referred to as “Lap,” a name that was thought to be conferred upon them by the Swedish Vikings. The name stuck and eventually spread throughout the region. Sami, of course, prefer the name Sami. Similarly, the land where they live—Norway, Sweden, Finland, Russia—is called Sapmi, not Lapland as it was historically known.

Inuit have had a long but infrequent contact with Europeans. This begins with the Norse, who the Inuit encountered during the 12th or 13th century. The Norse lived in communities further South in present-day Newfoundland but eventually returned, leaving few traces. One of the few is at L’Anse aux Meadows, Newfoundland. Equally profound is the small wooden sculpture of a Norse found on Baffin Island that dates to about 1250 AD. Archaeologists believe it was done by an Inuit artist and is the earliest evidence of a representation of contact. The man wears a long tunic with a border along the base and with a split at the bottom. There is also a cross hanging down over the chest or even emblazoned on the front of the tunic. The man is hooded, a sensible precaution on Baffin Island. I once had an Inuit art student say this was surely a “white” guy. “Why?” I asked: because the representation is a skinny man. Inuit, he said, picture themselves as round and robust.

Dr. Nina Vincent

According to European Historical accounts, it is told that the Americas were “discovered” when Christopher Columbus and his crew attempted to chart a route and oceanic passage to India. For this reason, Native people living in the continent were called “Indian” by these naval explorers. Today this term is intensively criticized, not only for the lack of meaning and relation to the Nations and Peoples living in this immense land mass that dwarfs Europe in size, but because of the generalization and how it has been used throughout history to homogenize diverse groups into a colonizable whole. Nevertheless, the term is still largely employed in South America, even by Indigenous folks. Yet, increasing critical debate and Indigenous participation in government and the formulation of laws, government policies and educational parameters have made a considerable impact. Amazonian Indigenous Writer and educator Daniel Munduruku often addresses this topic during his public discussions and certain audiences are persistently taken aback:

“So, I want to say that, despite my Indian face, my straight Indian hair, my Indian eye [puxado], my Indian cheekbones and this fit Indian body, I’m not an Indian. And I’d say more: there is no Indian in Brazil. (…) The Word Indian means absolutely nothing. If you look it up in the dictionary, it says it is “the chemical element no 49 on the periodic chart. Which Indian is celebrated on April 19th? Its an imaginary Indian. Not a real Indian. This Indian that was constructed during the nation’s formation doesn’t exist. Hence my affirmation: I am not and I don’t exist.”

The generic idea of “Indian” has been developed for centuries and usually goes one of two ways. Either a romanticized view of an “Indian” who is pure, untouched, and unspoiled good savage, or a wild, lazy, untrustworthy, godless retrograde savage who is an obstacle to progress and development. Both images are consistent cultural representations in visual culture and the arts, from the onset of colonization up until today. In Brazil, the Romantic period created icons of literature and painting that solely depict a version of Indigenous cultures that end up deceased, as if disappearance was inevitable. Several stories, both documental and fictional, mention the Amazonian territory as dangerous but magic, including the long-lasting legend of the Eldorado: a golden city filled with precious stones hidden in the heart of the Amazon.

None of these projections consider the real lives of Indigenous Amazonian peoples and their diversity. Munduruku continues his explanation with a question: “What defines who I am? My identity, right? My name, how I present myself to people. It’s how I identify myself, and in that case, I say I’m not an indian. But I am Munduruku. Being Munduruku is different from being Indian. And is different from being Wapichana, Kaiapó, Xavante, Brazillian. Being Munduruku is having an ancestrality, a way to read the world, a way to be human that is different from other People. (…) In Brazil only, there are 307 distinct Indigenous peoples, represented in all Brazilian states speaking 276 Indigenous languages.”

Most Indigenous ethnic groups from the Amazon are called by names given to them by their “neighbours,” which are adopted by the colonizers, which is a similar process to what occurred to the Inuit/Eskimo and Sami. Only recently have they begun to defend their right to be recognized in their own language and naming mechanism. It is a significant political achievement, but not everyone engages in this debate. How many of the names came to be is an important story. The people formerly known as Kaxinawá, who live between Brazil and Peru, were named by other groups that live in the region. The name translates into English as “the people of the bat.” Today they call themselves Huni Kuin, which loosely translates to “real people.”

Citation

McMaster, Gerald and Nina Vincent. “Epistolary Four: Contact Zones and the Interpretation of Language.” Arctic/Amazon: Networks of Global Indigeneity, Toronto: Wapatah Centre for Indigenous Visual Knowledge, OCAD University, 2022.

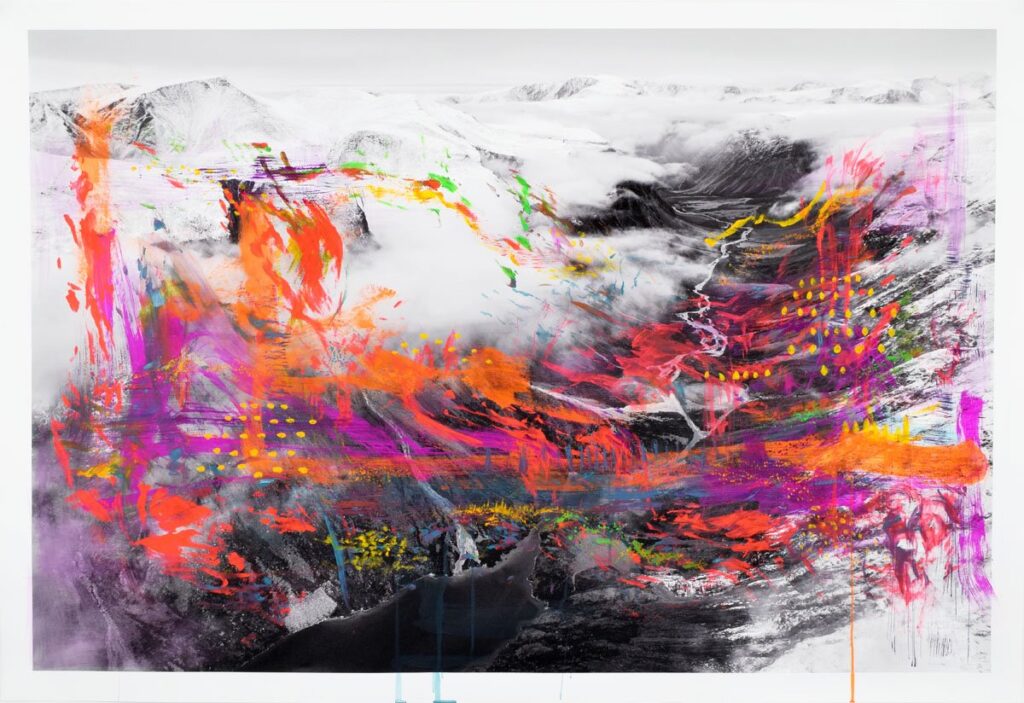

Image: Niap, “Untitled,” 2019, archival pigment print and acrylic on paper, Marion Scott Gallery, Vancouver

Arctic/Amazon: Networks of Global Indigeneity and accompanying digital educational resource are offered through the generous support from a SSHRC Connections Grant,

The Appleton Foundation, The Jack Weinbaum Family Foundation, Nancy McCain and Bill Morneau, Michael Audain, Kiki and Ian Delaney, Michelle Koerner,

and Jamie Cameron and Chris Brett.