Land Relations.

Indigenous communities maintain a deeply rooted connection to the Land, bound by tradition and ceremony. In the words spoken by Yube Huni Kuin to at the 2019 Arctic / Amazon Symposium to illustrate the implicit connection between Land, art, and culture: “Art has the power to not just exchange but also strengthen our territory’s culture.” Or, as Sheila Watt Cloutier writes: “We Inuit simply cannot have personal freedom…we cannot have choice if we don’t have the right to be cold if our homeland and culture are destroyed by climate change.”

Knowledge Exchange Workshop.

Dr. Gerald McMaster and Dr. Nina Vincent are joined in conversation by Ailton Krenak to discuss the profound importance of the Indigenous Ontologies and ways of being that stem from the relationship with the Land, and the idea of “forestzenship” as opposed to citizenship. The workshop also touches upon Ailton Krenak’s historic speech on September 4, 1987 at Brazil’s National Constituent Assembly. An important moment for Indigenous peoples in Brazil, the speech still resonates today – for some as “performance art” and for others as a groundbreaking use of Indigenous language and art as political resistance.

Harald Gaski

Harald Gaski was born and grew up on the river Deatnu in Sápmi, on the 70th latitude in the northernmost county in Norway. Gaski is an author, editor, and a professor in Sámi literature at Sámi allaskuvla (Sámi University of Applied Sciences) in Guovdageaidnu, Norway, and a professor in Sámi culture and literature at UiT – The Arctic University of Norway.

Harald Gaski. Photo by Bjørn Hatteng, UiT.

Resource Package.

The Arctic/Amazon digital resource is a free educational tool, featuring an abridged version of the Arctic/Amazon: Networks of Global Indigeneity Epistolary Exchange and a series of four virtual Knowledge Exchange Workshops led by the two principal authors – Dr. Gerald McMaster and Dr. Nina Vincent. This document is offered by Wapatah Centre for Indigenous Visual Knowledge as part of the publicly available digital resource and as a companion online tool accessible alongside the Arctic/Amazon: Networks of Global Indigeneity publication.

Arctic/Amazon: Networks of Global Indigeneity is co-authored and led by Dr. Gerald McMaster and Dr. Nina Vincent.

Dr. Gerald McMaster

Gerald McMaster, O.C., is one of Canada’s most revered and esteemed academics. He is a curator, artist and author, and is currently professor and Tier 1 Canada Research Chair of Indigenous Visual Culture and Curatorial Practice at OCAD University, where he leads a team of researchers at the Wapatah Centre for Indigenous Visual Knowledge. He is nehiyaw (Plains Cree) and a citizen of the Siksika First Nation.

Dr. Nina Vincent

Nina Vincent is a Brazilian anthropologist currently working at the National Institute of Historical and Artistic Heritage (IPHAN). Her work focuses on intangible heritage preservation, museum studies, intersection of contemporary art production and community partnership building, Indigenous art and knowledge, and cultural perceptions of nature and politics.

EPISTOLARY THREE: GLOBAL INDIGENEITY AND LAND RELATIONS

Dr. Gerald McMaster

“Sami people are very similar to us, even their land is very similar, except the fact that they have trees.” – Trudy Tulugarjuk.

I was quite moved by the above statement. It reminded me of the reactions by the participating artists in the 2019 Arctic / Amazon Symposium, who upon meeting each other for the first time remarked on their similarities. After the Symposium, we made the decision to expand to include artists and writers from other circumpolar Arctic regions, such as Greenland and Scandinavia, as they would bring additional perspectives to the global Indigenous.

The entire circumpolar Arctic region has been similarly under continuous colonization from Western powers for centuries. Since the early 2000s, the Indigenous Samis of Finland, Norway, and Sweden have been working together on the Nordic Sami Convention, an agreement that addresses Saami rights to self-determination.

Though the Sami and Inuit originate in the Arctic, their logic as connections within a network of “global indigeneity” is only quite recent, especially when it comes to land, identity, and self-determination. Indigenous peoples in the circumpolar Arctic occupy seven of the eight Arctic states, while making up about 10% of its total population, or four million inhabitants. These modern geopolitical borders have often divided communities, thus creating transborder identities that are notable for the relations that continue on either side of the border, regardless of the nation who lays claim to their lands. These are inherent supranational cultural groups that exceed the boundaries of the Nation-State.

Inuit, for example, live across contemporary geopolitical lines and are politically tied to Russia, USA, Canada and to Denmark (Greenland). They begin in Russia with the Siberian Yupiks. In Alaska they are referred to as Eskimo and have accepted the term. In Canada, Inuit live in the Inuvialuit settlement, comprising (Northwest Territories), Nunavut, Nunavik (Arctic Québec), Nunatsiavut (Labrador), and Greenland. Similarly, Sami live across the northernmost parts of Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia. They call this region Sapmi, which identifies the cultural region they traditionally inhabit.

Inuit are widely spread out and have focused their efforts on establishing regional governments, while Sami have focused on shared rule or integration within broader non-Indigenous government structures. Even in their difference in activating self-determining forms of governance, Inuit and Sami are united in their emphasis to protect the natural environment, preserve their cultural identity, and maintain political autonomy within settler colonial states.

In 1999, the most important territorial claims in Canadian history led to the creation of Nunavut, meaning “our land,” which became a homeland to many Inuit across Canada. Inuit are the majority population and so their position of power appears a bit more secure, though Nunavut does not have the same political powers that all other Canadian provinces enjoy. The population does, however, enjoy the social benefits of circumpolar citizens, with the exception of Russia.

Despite these modern advancements Inuit like other circumpolar Arctic Indigenous peoples are still under the authority of colonial agendas, which are often focused on natural resource extraction and northern border security. These are privileged white interests.

Dr. Nina Vincent

The situation is both similar and different from Amazonian Indigenous peoples. For starters, the Amazon experienced a different type of colonization that continues into today in varying intensities. South America was invaded by Spain and Portugal in the sixteenth century. A Papal Bull traced an imaginary line and divided the continent between the two countries, which was nearly entirely unknown to them at the time. This resulted in most of South America falling under Spanish domain, while Brazil became a Portuguese colony. Colonialism and the economic theories that supported it at the time defended a type of colonization based on exploitation, which was different from the mercantilist economy imposed on the settlement colonies of the British Empire. Those aspects are neither better or worse, but they do shed some light on the differences in the colonial process.

When travelers from the Iberic Peninsula came to these lands and encountered Indigenous peoples living all over the continent, there was no Treaty put in place. There was no intention to establish trade with another autonomous society, to develop agriculture, incentivize settler immigration or create a local consumer market, there was only the interest in extracting resources. Wood, gold, and metals were the first exploits. Because of its remoteness and the difficulty of navigating it for outsiders, the Amazonian Rainforest was the final part of the continent to be colonized. In most countries the colonizers encountered and battled with Andean native peoples, the most well-known are the Incas, Mayas and Aztecas. In Brazil, Indigenous peoples from the coast, such as the Tupinambá and the Guarani, resisted colonization and sustained significant territorial, demographic and cultural losses as a result.

There are records of Indigenous slavery occurring during the colonial period in Latin America. For centuries, Indigenous peoples have been displaced. Oftentimes they have become attracted to missionary camps, destitute of their culture and sense of belonging, searching for support.

Encircling “modernization” of the Amazon is responsible for furthering the precarious situation of Indigenous communities. Many investments were made in the surrounding areas in order to extract natural resources from the region, without care for sustainability or for the original inhabitants of the land. By the 20th century, the extraction of rubber was the greatest source of revenue in the region, making a few settlers and foreigners very rich while attracting a chaotic migration of workers from other regions to the rainforest. These economic migrants were exploited under conditions analogous to slavery, sustained by debt to the “patrões.” When cheaper latex started to be produced in southeast Asia, the economy declined. Farms and new cities were abandoned and a trail of poverty was left in the wake of the economic boom.

Many Indigenous people worked in this industry, becoming “seringueiros” alongside the immigrants, and from this mixing of people and cultures sprung a local Amazonian culture strongly connected to the land and influenced by Indigenous habits and beliefs, but carrying the marks of the erasure of their ancestrality.

Citation

McMaster, Gerald and Nina Vincent. “Epistolary Three: Global Indigeneity and Land Relations.” Arctic/Amazon: Networks of Global Indigeneity, Toronto: Wapatah Centre for Indigenous Visual Knowledge, OCAD University, 2022.

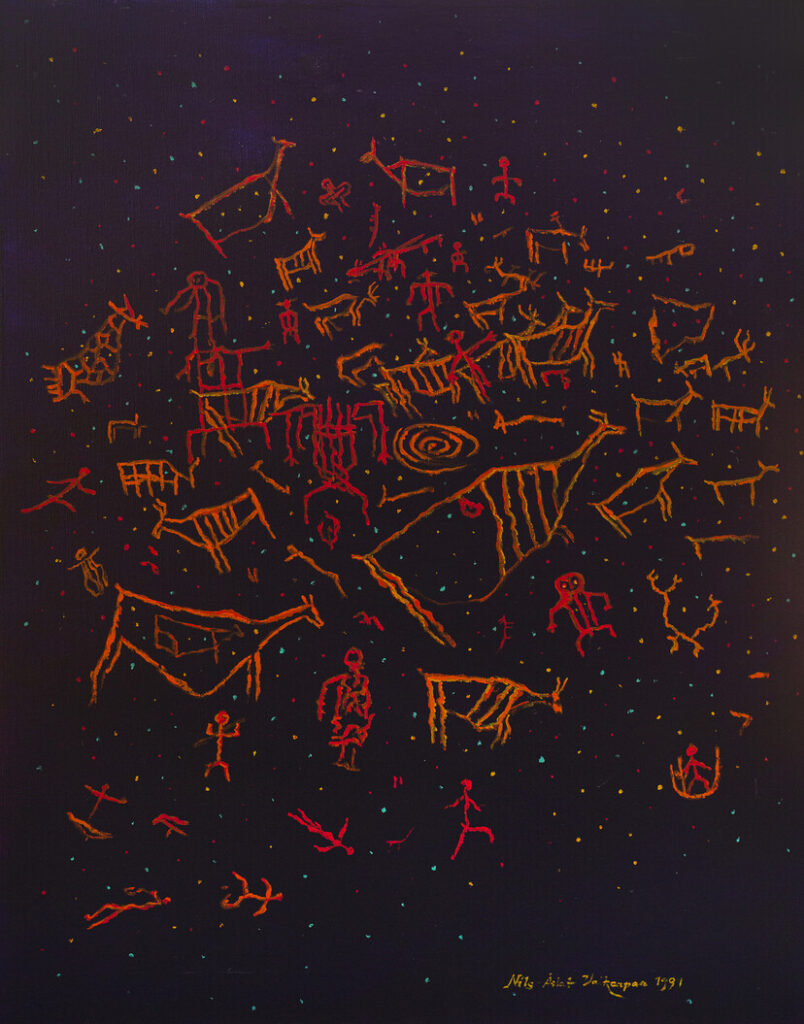

Image: Nils-Aslak Valkeapää, No Title, 1991, the municipality of Kautokeino Collection

Arctic/Amazon: Networks of Global Indigeneity and accompanying digital educational resource are offered through the generous support from a SSHRC Connections Grant,

The Appleton Foundation, The Jack Weinbaum Family Foundation, Nancy McCain and Bill Morneau, Michael Audain, Kiki and Ian Delaney, Michelle Koerner,

and Jamie Cameron and Chris Brett.